The Poetic and Practical Art of Pickling

by Aya Burton

Recently, there has been a resurgence of interest surrounding the art of pickling and food preservation. Yet, at the same time that pickling is a high-velocity trend among foodies, it is also a natural, millennia-old practice. Refrigeration, after all, was invented only a little over a century ago, in 1913. Prior to that, essentially all food was local, and nothing was wasted. Pickling nowadays, however, can look quite different than it did in years past. The jars that you see lining supermarket shelves often contain chemicals to preserve the food sealed inside, and traditional, intensive pickling processes have been replaced by time-saving preservatives. Time, however, is an irreplaceable ingredient in homemade pickling recipes. The days, weeks, or even months that pass while waiting for a jar of fruits or vegetables to ferment are integral to the process and the art.

I refer to pickling, or preservation, as an art because of the commitment, innovation, and individuality that can go into each batch. Homemade preserves are special in that they capture the essence of the home cook who made them, varying based on the individual’s tolerance for spice or preference for particular flavors. Homemade pickles are also an inherently nostalgic food—perhaps even an emotional food, given their ability to restore memories of summer, picnic spreads, and possibly secret family recipes. With the twist of a cap, you can have summer sealed, labeled, and salvaged, even as the air cools and winter moves in. Beyond their poetic nature, however, pickled preserves are a practical food with a history of preventing hunger through colder months and providing a reliable source of sustenance in arid regions where fresh produce can be scarce.

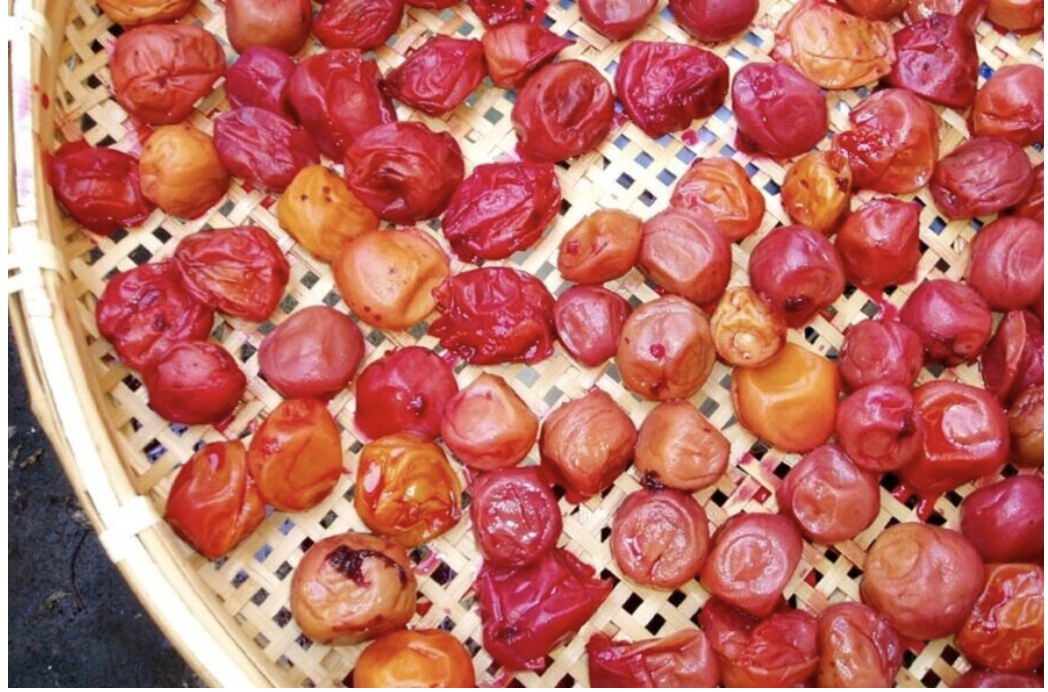

On the most basic level, pickles are created by immersing fresh fruits or vegetables in a salty brine or acidic solution until they are no longer raw or vulnerable to rotting. In the past year, many folks have started stocking their shelves with rows of homemade preserved goods.

This renewed interest in pickled foods can be partly attributed to the items’ resistance to spoilage, meaning they do not expire on the shelves of a pantry or supermarket. This preserves not only the food itself, but also the money that would be wasted by their decay. In some ways, pickling and food preservation simply have to do with being a good capitalist.

Looking back in history, one can observe periods when values like thrift and sustainability especially governed people’s habits, including their diets. In the twentieth century, during World Wars I and II, victory gardens emerged in private backyards and residences as an initiative to prevent food waste. An ethos spread across the United States that to grow and preserve one’s own food made one a contributory and patriotic citizen. Victory gardens supplemented people’s rations, and families often preserved the fresh produce grown in their private plots, resulting in the slogan, Grow your own, can your own.

In examining Americans’ food purchasing patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic, similar trends can be traced. This pattern indicates an increased reliance on canned and preserved foods. Much of the general public could be seen flocking to supermarkets to stock up on shelf-stable products—it was not exclusively “doomsday preppers” gearing up for the “worst of the worst.” Grocery store aisles emptied of products and people feared for their food supply. The collapse of our food system during COVID-19 clearly revealed its inherently flawed and dysfunctional state. Lisa Raiola, President and Founder of Rhode Island’s premier culinary incubator Hope & Main, explains: “The U.S. spends less money per capita on food than anywhere else. This is because the government subsidizes cheap products like corn, soy, and rice that have completely saturated the market and the foods we consume.” To mitigate the risk of future food shortages or scarcity, we need a diversification of the food system at the local level. This means investing in local food systems without long supply chains.

A local food system is a just, sustainable, and healthy one. More and more, we are seeing health-conscious consumers seeking less processed foods. Beyond produce, they want pickled goods that are clean products, unriddled with the preservatives so often used to extend shelf life. “If you don’t support local, it's not going to stick around," Raiola says. "It'll be eaten up by bigger companies with bigger resources." Spending money on local food is vital to the maintenance of a vibrant local economy and community. It also ensures that you are purchasing real food—free of fillers and preservatives—and helps provide a living wage to an actual person.

Beyond the U.S., almost every culture in the world has developed its own form of the pickle using local staples. In several countries, pickled foods have always been central to cooking. Many people may be familiar with kimchi, a standard in Korean cuisine. It is a side dish made traditionally from fermented, salted, and seasoned napa cabbage. The fermentation process and the hot chili pepper gochugaru give kimchi its signature spicy, sour flavor. Since it is naturally fermented, kimchi is full of healthy bacteria, or probiotics, that boost immunity and aid digestion. These days, kimchi is most typically fermented in the refrigerator, and the longer it ages, the more pungent it becomes. Locally-made kimchi usually tastes more authentic and is free of the nitrates and other preservatives that non-refrigerated versions sometimes use.

Achar, a South-Asian pickle native to the Indian subcontinent, is made from a range of vegetables, fruits, and meats preserved in brine or mustard oil. A condiment staple, achar can be used to spice up any meal. The produce most commonly used to create achar includes regional green mangoes, lemons, limes, ginger, and eggplants, with the constants usually being chili pepper and fenugreek seeds. Homemade achar is prepared in the summer and matured by sunlight exposure for up to two weeks. Since it is time-intensive to make at home, and store-brought jars are often loaded with salt and preservatives, local, small-batch versions of achar tend to be the preferable option. Prepared the way that it should be—fresh in someone’s kitchen, rather than mass-produced in a facility—bottled achar tastes fiery and complex, serving as the perfect savory complement to rice, stews, paratha, or any dish that needs a bit of brightening.

Encurtidos is too broad a term to translate to a single English equivalent, but is essentially the Spanish word for “pickles” or “relish.” Similar to how Korean kimchi can involve a wide variety of vegetables, encurtidos take on many variations and are made in several Latin American countries. Most recipes use vinegar or citrus juice as the pickling agent, along with onion and oregano which lend an acidic, herbal flavor. Frequently pickled vegetables include red onion, cabbage, carrot, cauliflower, and jalapeños. Though typically used as a garnish for dishes like tamales or tacos or to cut through fatty meats like barbacoa and carnitas, encurtidos can also be enjoyed on their own as a snack. Homes and restaurants often have large, colorful jars of homemade encurtidos sitting on the tables.

There is something special about a food item prepared differently all across the globe, and that varies even between local regions and cooks’ personal preferences and executions. What remains constant is each jar’s power to remind its consumer of home, summer, or a family member’s unwritten recipe—the drama, nostalgia, and innovation unique to the time-tested pickle. Homemade versions create a one-of-a-kind eating experience, with their bright bursts of color artfully seasoning any meal. Cleansing the palate and clearing the mind with each tangy bite of acidity, pickled goods remain a hot food commodity even centuries after taking to the culinary stage.